©

Fossil of the Month

Fossil des Monats

Fossile du mois

JULY 2021

The winner will receive a Certificate of Commendation

PETE WINS WITH THE CORRECT ANSWER September 2020

“My guess is that these are the fossil remains of the burrows of the mud crab Ophiomorpha beaumariensis”.

September 2020

Our third competition. What do you think this is?

This specimen is a branching tubular structure. Where it is not weathered, the exterior of the specimen has a nodular pattern. It is common in the Beaumaris Sandstone from Rickett’s Point to Black Rock and can be easily observed on the wave cut platform. The diameter of the coin (centre right) is 23 mm. The first to guess the true identity of these fossils will be given a free copy of the Fossils of the Urban Sanctuary from the Bayside Earth Sciences Society. You have until Oct. 15th

August’s “unknown” was never going to be an easy. These structures formed about 2.49billion years ago, when the world was a very different to the present day. The dry land was bare of life. There were organisms in the seas and lakes, but these were Cyanobacteria, and although they did form colonial-like structures, they would not have produced these. At this time, the atmosphere alternated between aerobic (with abundant oxygen) to anaerobic (with no free oxygen). They are pseudo-fossils, produced by chemical, rather than biological or mechanical processes and are known as Belousov-Zhabotinsky Rings. These are chemical fronts that form in non-equilibrium conditions. The chemical fluctuation in the environment (an iron-rich sediment with fluctuations from high to low oxygen) produced the perfect conditions for these structures to form.

The responses last month were thoughtful, ranging from stromatolites (produced by Cyanobacteria) to bubbling mud (the closest… but not close enough!).

August 2020

August 2020: Our second competition. What do you think this is?

The responses last week have provoked a further quiz. This month’s unknown is even less well understood – even by geologists. These circular, ripple-like structures occur in the Dale’s Gorge Member of the Hamersley Group of Rocks in the Pilbara Region of northern Western Australia. Of great significance is that they are in rocks that have been dated as 2.49 +/-15 billion years old. At that time there were very few things living on Earth – the most common organisms being cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria still live today, and are responsible for producing the world-famous stromatolites in Shark Bay, Western Australia (see https://www.sharkbay.org/place/hamelin-pool/).

The beautiful structures in the image above are very rare, even in this remote setting; they are restricted to a layer only a few centimetres thick and are preserved in haematite, the primary ore for iron. Up to 50% of this rock is iron, making it a valuable deposit.

But what are these structures? Scale: The 1 euro coin is 23.25 mm.

These structures do have a name, but these details will not be released until next month.

The first to guess the true identity of these fossils will be given a free copy of the Fossils of the Urban Sanctuary from the Bayside Earth Sciences Society. You have until Sept. 5th

Send your answer to: baysidefossils@gmail.com

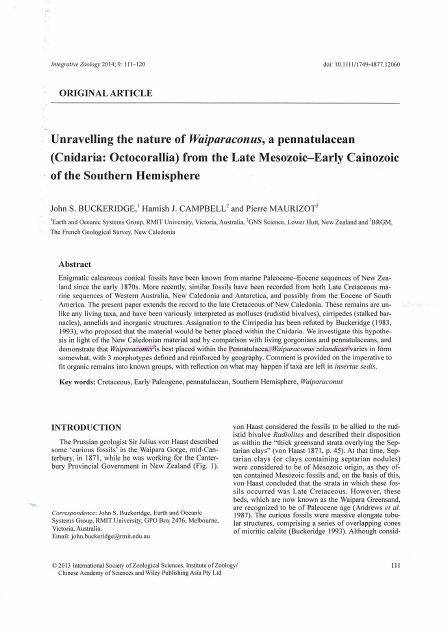

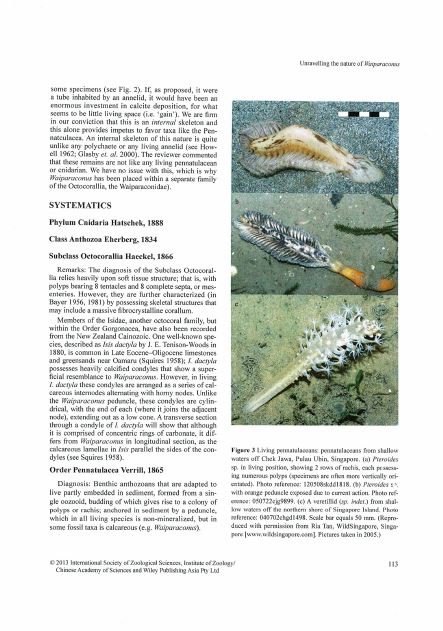

N.B. Last month’s specimen was not correctly identified, although we had some excellent responses. The fossil was the “sea pen” Waiparaconus zelandicus, a type of extinct octocoral. See Paper below.

July 2020: Our first competition. What do you think this is?

Sometimes even well-established palaeontologists find certain fossils difficult to identify. In general, humans interpret the fossil record on the basis of what we observe in the world around them. If no living organism looks like a particular fossil, classification can be very difficult.

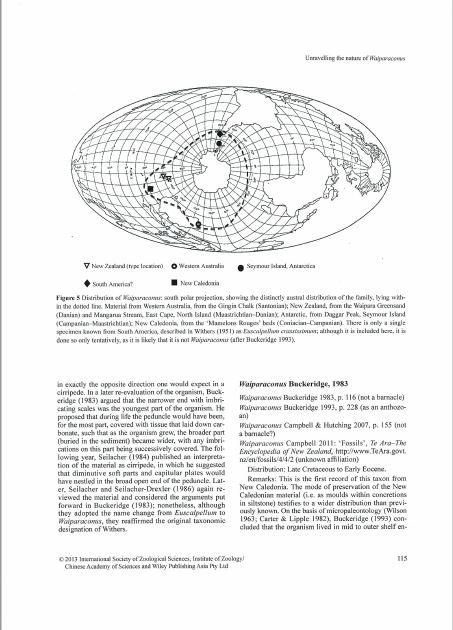

The above marine fossils became extinct some 40 million years ago. During their acme in the late Mesozoic, they were found living in low-energy, mid-shelf settings in what is now Antarctica, Australia, New Caledonia, New Zealand and South America. They are true citizens of Gondwana, the ancient super continent that existed in the Mesozoic.

These fossils have been interpreted by some as plants, by others as molluscs, worms, crustaceans and corals. Some have even considered them to have been formed by non-living processes.

Scale: The 1 euro coin is 23.25 mm.

These fossils do have a name, and their place in the “Tree of Life” is now well established; but these details will not be released until next month.

The first to guess the true identity of these fossils will be given a free copy of the Fossils of the Urban Sanctuary from the Bayside Earth Sciences Society. You have until August 5th

Send your answer to: baysidefossils@gmail.com

Sorry to advise that no-one came up with the correct answer, but this was a very hard one to solve. See below;

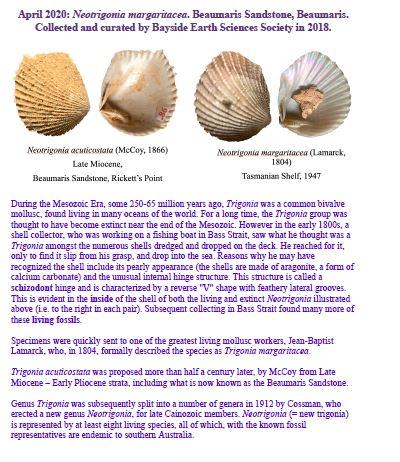

May 2020

April 2020: Cetacean vertebrae. Beaumaris Sandstone, Beaumaris. Collected and curated by Bayside Earth Sciences Society in 2019.

Once upon a time, some six million years ago, a small whale, probably much the same size as a large dolphin, was swimming in Balcombe Bay. For some unknown reason, it died. Perhaps it was diseased, for if it had been attacked by a larger predator, the bones we see in this image would probably not be aligned as they are.

After death, the whale’s body sank to the seafloor, where it was covered in sediment before scavengers had an opportunity to tear the carcass apart. What looks like a series of alternating vertebra and vertebral discs is actually part of a vertebral column of a young whale. Each vertebra in this example is made up of a larger primary vertebral body (about 50 mm long), with a thinner, ossified epiphysis at each end (each about 9 mm thick). If the whale had lived to become an adult, these three portions would have joined together, generally obscuring the suture between the components. This slab of rock, from the Beaumaris Sandstone at Beaumaris, contains the four partially ossified whale vertebrae.